Frames: Does Capitalism Enclose Art?

|

| Obnoxious Liberals. Jean-Michel Basquiat, 1982. |

Frames capture things. They entrap them with thick, ornate gold; heavy-set, and claustrophobic. But they also contain them. Whether there is frame or no frame, there is a sense of frame-ness, which arises as soon as it is possible for a frame to be there.

Contained or uncontained physically, the artistic object is always defined by the frame, whether it loudly announces its presence or not. Setting something in gold is very different, and carries different messages, to setting it in dull copper. The frame also constitutes its content. In relation to the rich gold, the delicate-hued picture appears washed out. Rather than balanced, it is faded, de-vivified. Inside a white frame, or stuck straight onto a white wall, it is predominant.

The decorative frame tells a story of its own. Every object is an artistic object. By placing a frame around a picture, we create a dialogue between the two. This dialogue might be sensical, or nonsensical. Pleasing, or displeasing. It may appear complex, or appear simple. And, the choice of frame, and hence the dialogue drawn on, might appear skilful, or unskilful. We can only be informed, particularly on this latter point, post-fact: that is, post-framing.

Frames generates facts, perceptual facts, in the same way that works of art do. One can respond to this generation in one of two ways. Firstly, one can attempt to negate it. This entails minimising, hiding, and withdrawing the facts, so as to let the work of art expand into space. There is one sense in which this is a sensible exercise. We whiten walls, flatten frames, enforce monochrome, or do away with physical frames altogether. Thus, we idealise. We attempt to abstract the object as much as possible. This can be thrilling.

|

| Suprematist Composition: White on White. Kazimir Malevich, 1918. |

On the other hand, it is also deeply futile. What is defined as environmental “neutrality” is determined by the culture in which one is presently embedded. Not only the global, temporal culture, “the culture of 2021”) but one that filters down to local levels – the nation, the town, the household – and even to the self; the collection of unique experiences bound up into consciousness. Yet even this consciousness is radically changing from minute to minute, drawing upon new parts of itself, as the clearing within the forest that represents possibilities of being continually shifts. Our framing of the picture – the mental or perceptual one – is constantly changing.

Our perception of the picture shifts with time, with cultural context, with individual whims (and emotion), with the literal frame, with – if you permit the extension – the metaphorical frame of the gallery space. It too can be gilded and ornate, or white and austere. Now we look at the picture and wonder how it can ever be one and the same thing. We haven’t even mentioned the titles or information you read before or after your encounter, which structure your understanding.

The psychological concept of affordances, developed by James Gibson, helps us understand how humans negotiate a human-perceived world. We see a stair primarily as that which we can step on, not a ninety-degree wooden protrusion. We see a handle as able to be grasped by a hand, to pull open a door or pull ourselves up out of a swimming pool. There is this sub-rational perceptual layer, which disappears when you think about things too hard. By going beyond the immediate layer of encounters with reality, we can build up logical structures that purportedly help us to understand the world of things-as-they-are, beyond the veil of human perception. This is the world of quantifiable phenomena, where water is composed of hydrogen and oxygen and light travels at a finite number of miles per hour. We can perceive neither of these facts, but nevertheless it is useful to us to dwell on such things from time to time, especially to improve the quality and duration of our lives with technology.

|

| Relativity. M.C. Escher, 1953. |

It is a common belief, one which Graham Harman espouses in his book on object-oriented-ontology, that poetry captures that which cannot be captured by quantitative measurement. This belief holds that the arts penetrate the layer that necessarily exists between humans and the real state of the world through an allusory technique. That is, they indirectly broach the topic at hand in the manner of metaphor to reveal new levels of truth.

What art accesses is not a world beyond, but a world before us. The poetic and the scientific sit in exactly opposite relations to the human than what Harman, and the great Spanish philosopher he draws from, describe. Art is the immediate, and any attempt to put its production beyond ordinary human comprehension is misguided by cultural structures that place art within the gallery. Whilst the gallery may isolate, idealise, and subdue dialogues in ways that elevate the oneness of the artistic object, they also separate the world of creativity from the everyday, functioning as what the philosopher Foucault calls a heterotopia. Because the utopia cannot exist, except within the minds of perceivers and conceptual frameworks, the heterotopia is fashioned to embody some of its essential qualities. Spaced out from everyday life, it nonetheless is habitable by humans, although it sometimes marginalises them.

The gallery space idealises paintings and sculptures to be like objects in the utopia, but does so imperfectly. The cultural enmeshing of idealisation techniques entails that all attempts will be framing, and all galleries will be heterotopias. Just as the graveyard cannot be the perfect memorial for the dead, because the placement, arrangement, and adornment of the corpses is conditioned by the living, so are exhibition halls not perfect monuments to the greatness of art. But we have said we should not believe their pretence, which seeks to isolate the everyday from the artistic.

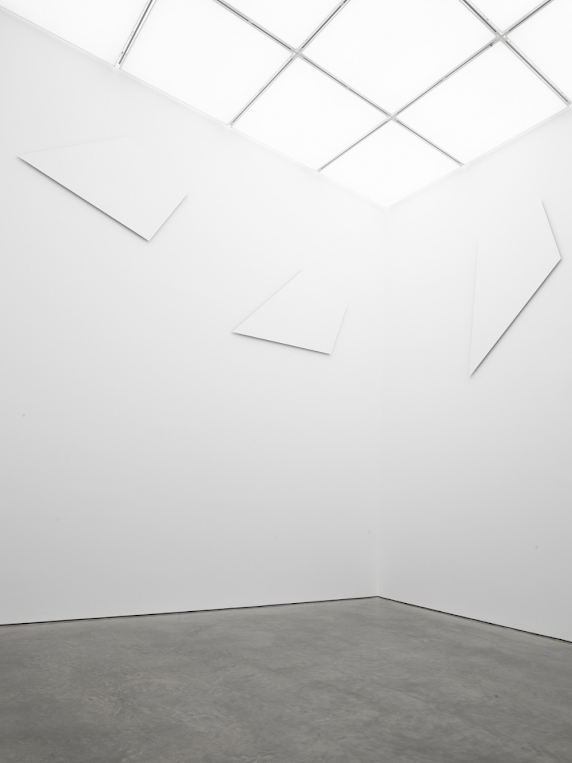

|

| 9x9x9 room. The White Cube, Bermondsey. |

What we have in the muting of dialogues is a grand focalisation on the life of the artist. An artist cannot have his pieces in a gallery without making a name for themself. What is on display is the artistic object, but what is framed is the product of an artist. That artist themself serves as a framing.

We can have all the beauty of nature; waterfalls, mountains, the iridescence of a beetle, or bright colours of leaves in autumn; without a creator. We do not have to presuppose the framing of this beauty by a mythical originator.

Yet when a beautiful work is placed within a gallery, we feel the need to attach nomenclature to it. Not only does it need a title (even if the negation of “untitled”), but a source – a year, and a human that has brought it forth. Would be attribute the creation of a beautiful nest to a bird, and place it within a gallery? I think not. Nor would we temporalize it; although we may perhaps speak about the origin of the bird for classificatory purposes. Such is our anthropocentrism.

What the gallery does is perform an exercise of adulation. Flat Ontology, as elaborated by larvalsubjects.com, holds that the deprivileging of humans as the predominant objects of concern in the universe is a necessary step in attaining a more accurate understanding of the world. We cannot have a clear picture of the reality behind things unless we step down from the podium of self-absorption, whether it be congratulatory or putative absorption, and recognised stones and cows as beings in their own right rather than objects to be technologized, commodified, and used.

Yet this “modern” understanding of the world, the focal point for so many criticisms, is rarer than one might think. It is true of capitalistic structures and the deployment of business operations. The attainment of maximum concrete gain for minimal expenditure of concrete resources dries such practices at their exponentially perpetuating core. But this is not the understanding of the world achieved when one goes for a walk in the park, or even travels to work on the train. This is a position we assume when we are afforded the opportunity by ideological, external structures which arise out of complex organisations of humans that found, delimit, and ground these structures. Commodification cannot exist without transport networks that facilitate trade, which cannot exist without the large, centralised bodies known as universities and research institutes that output technological progress. Intercontinental colonialism cannot exist without the ability to rapidly manufacture boats.

|

| Self-Portrait with Bandaged Ear. Vincent van Gogh, 1889. |

Although the state in which we can appreciate the beauty of the non-human world may be more natural to us, it nevertheless, today at least, is framed by ideological structures. When we go for a walk, we inhabit a defined concept, with predetermined properties. These properties include level of physical strain, approximate duration, the expectation of some kind of route, and the interpretation of “the walk” as the break in the productive cycle. The walk is seen as a tool, which enables one to mollify aberrant desires and, according to social acceleration theory, perpetuate the cycle of rapid, immediately “fruitful” activity and accumulation. It is only within these kinds of interpretative framings that the appreciation of nature can be structured into routines and time, and thus, one’s conscious accumulation of perception of the world.

Art is no different. We see art in the everyday on the off-chance that we are struck by something unusual, or unusually beautiful. But these kinds of opportunities do not afford us the ability to look consistently at objects and say they are art.

Galleries may be a grand contextualisation, an illusion with pretensions, but they also serve to provide us with objects and environments that we have a greater chance of perceiving as art. Removed form the ugly or unsuited frame, an instance of creativity can shine through in maximal glory. Whilst art markets and collectors, curator and critics may be subservient to the demands of capital, the simple fact of the matter is that the quotidian is rarely encountered in ways that evince beauty.

Able to be placed in the context of insightful descriptions, beautiful, taciturn findings, and the perceived attention of others, the artistic object is adorned with all it needs to reflect the beauty in the eye of the beholder. If there is a failure, it is the failure of the art to be unanticipated, to be genuinely refreshing and surprising, to perhaps challenge its frame. This is not a problem for space, it is a problem for creativity itself. In its careful dialogue, one may have to intrude upon the other.

_

Endnotes

Umwelt is a German word that describes the concept of the non-neutral environment. This exhibition deals with the theme very well.

The great Spanish philosopher is Jose Ortega y Gasset. Harman's book is, despite its misgivings, very good.

This piece is inspired by readings in ontology, phenomenology, and on Martin Heidegger's philosophy. In fact, it's actually a response to one of his essays.

Comments

Post a Comment