Tullio Crali: Master of Motion

Crali, along with fellow Italians Severini, Boccioni, Depero, Carrà, and heavyweight Fillipo Marinetti, participated in the Futurist movement his entire life. The art movement vociferously expressed the technological advancements that modernisation in the early to mid-20th century brought to the western world. Speed was a tremendously important concept to public and intellectual thought in this period, and futurism often deals with depictions of motion.

Motion is most defined as the changing position of an object over time. When both the objects change and the perception of time change, motion is conceived of by beings-in-the-world in a different manner.

The objects that inhabited everyday life radically changed in the 20th century. As the military-industrial complex was brought forth into its most virulent phase, everyday life became occupied by the car, the motorbike, and the aeroplane. Motorsports became a macho-centric fixation, and flight craft commanded the course of history with the lethal use of their armaments. Not only were these objects radically different from the horses and dreamy balloons that preceded them, but they also reshaped the anthropic understanding of time. This took a literal form in the preceding century, when the establishment of railways impelled the propagation of a global system of timekeeping. Prior to this, every town was set to a different, astronomically accurate time standard — which would make planning travel according to the localised timetables needlessly difficult. In a more general sense, the removal of chronological constraints on commutes, trips, and holidaying changed the face of common life, opening up possibilities and interconnecting humanity to a far greater degree than before. This had wide ranging economic and social benefits — though of course, at the cost of global environmental health, and the preservation of esoteric aspects of non-dominant cultures. The impact of the road and the car on the proceedings of criminal life is explored in Nabokov’s novel Lolita, where the grandiloquent paedophile Humbert Humbert continually flees authority and concrete (social) place with his victimised stepdaughter.

But what does this have to do with Crali?

|

| Tricolour Wings, Tullio Crali, 1932 |

Crali’s depictions of movement, with sweeping lines and bold colour, offer a window into the furore that was occurring in the mind of an artistically gifted fifteen-year-old amid 1920s Italy. Crali’s paintings appear incredibly precise at first, one block of carefully shaded or unshaded colour separated from another as if by a ruler. But first glance deceives: his lines bear the roughshod resemblance of something drawn quickly; hastily; as if in a rush. The very brushstrokes embody the frenetic yet carefully directed energy of a race car, as it rounds the apex of a bend. He goes beyond the prototypical cubist mantra, by not just representing multiple perspectives within a 2D plane, but by placing forms in relation to each other using methods that emphasize their entanglement. The leading edge of a car hood becomes a tyre, a shadow on the road, and then the line slips beneath the body’s smooth red form to demonstrate the miles and sundry objects that the car eats up

Futurism is a cultural movement from which we can draw an indelible line towards phenomenology. Maurice Merleau-Ponty’s intellectual capitulation to Gestalt psychology takes the entanglement of objects, like the tyre, hood, and shadow of the car-as-experienced, as inseparable. Contrary to what those of a broadly objectivist stance would claim, the race-car as observed here cannot be broken down into a mere assemblage of forms — it is the parts together, configured as they are, that make it up. It is perhaps absurd to talk even of parts in too precise a sense.

Merleau-Ponty devotes a notable part of his most significant work, Phenomenology of Perception, to the motion of the body. As he posits that conscious beings can never occupy a transcendental, privileged position — they must always interact with the world through their fleshed-out bodies — the motion of the body is therefore important to his narrative. However, to articulate views on the motion of distantly external objects, we must turn to process philosophy, which promotes the belief that the metaphysical basis of the universe is change. Aspects of the field are appealed to by diverse figures such as Deleuze, Marx, Heidegger, and Latour, but it was Aztec scholasticism that seized it most readily as a first principle. It would be incredulous to say that Crali had in mind indigenous Mexican thought when feeding his faintly infantile obsession with “things that go fast”, but the cynosure he chooses speaks of a personal worldview that cannot escape the vividity of motion. This motion does not occur in spacetime, but rather, creates it; in concordance with the theories of quantum gravity that the foremost physicists deal with today.

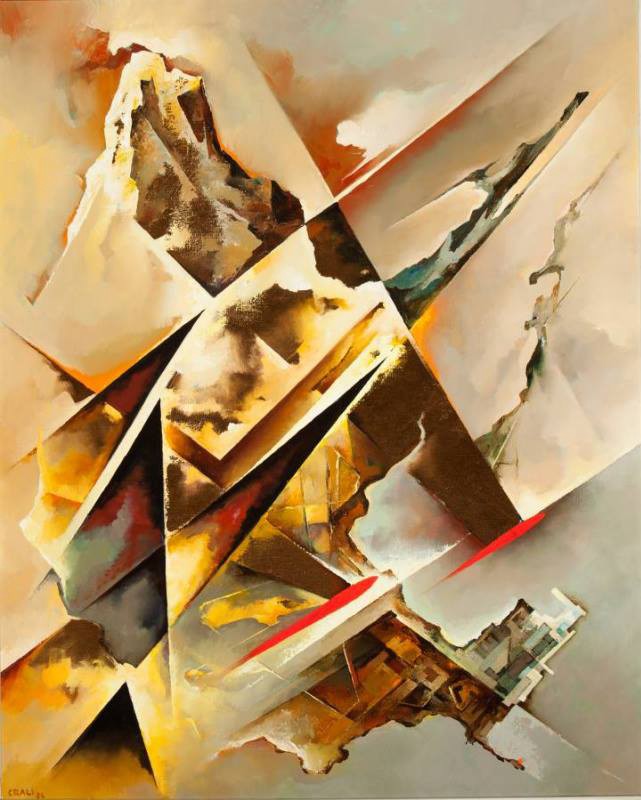

|

| Supersonic, Tullio Crali, 1986 |

The title of the exhibition is telling: the Futurism that Tullio encountered when he was fifteen was never let go of. In time his mechanical transfixions morphed, with the increasing speed of his subjects begetting truly supersonic works, and his occasional cavorts into sky and cityscapes explicate new ways of appropriating cubism’s geometrical qualities. However, his style remains stagnant, accomplishing minimal perspectival revolution; utterly odd when one considers the monuments of global history that his career spanned. The impact of the Second World War was clearly minimal for him: or perhaps the milieu that it gave to the Weltgeist that early Crali contemplated, reached back into the interwar years, and made the decades before a seamless piece of their fascistic puzzle. Either way, the movement died with Crali, and inspired understandably sporadic interest once the Paris Peace Treaties had been signed. Crali faced non-trivial estrangement due to his collaboration with Mussolini’s regime, and one cannot help but feel that once the artist left the Republic of Salò, he lost the ability to osmotically reproduce the social conditions of the world around him. His utopian cityscapes, produced largely in the 1930s, rise up, glass and steel, out of the earth, as if growing from the bodies of the winsome wooden constructions they replace. These Nietzschean thematic plays, in which creation builds itself and emerges upon destruction, are troublesome when conscious of their methodological similarity to the works of Albert Speer, the Nazi architect who designed the unrealised buildings that participated in the ideology of the Thousand-Year Reich. But if Crali soon forgot this nastiness he (skilfully) reproduced, no novel contemplatory object replaced it. Rather, his aeropainting spiralled higher and higher into the skies, as his work began to lose its once masterfully honed edge of radical semi-abstraction.

Truthfully, there is nothing wrong with this exhibition. If one approaches it as a collection of Futurist works, we are presented with a storied and fascinating history of one of its most pre-eminent painters. However, the superlative quality of the works that inhabit the first room will necessarily leave unsatisfied the whetted appetite of the viewer that moved into the second. Crali’s earliest works turned on something dynamic; a phenomenological bent and an understanding of historical narrative that conjunct are both rare and remarkable. And for that reason, I would thoroughly recommend a visit.

Tullio Crali: A Futurist Life is showing at the Esoterick Collection, Canonbury until 13th September.

Comments

Post a Comment