Towards a Decentralized Future

|

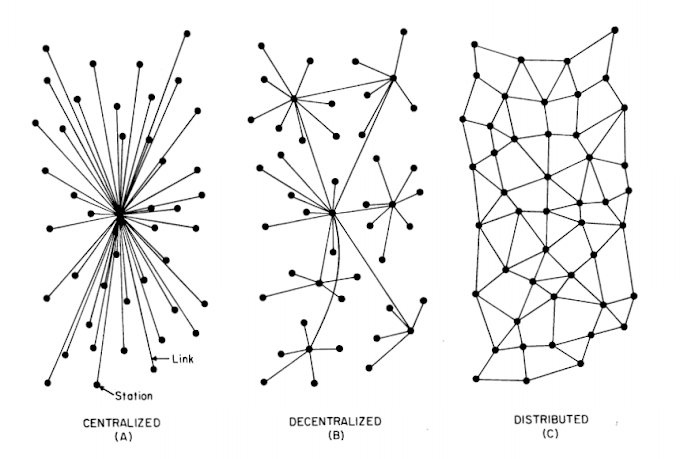

| Paul Baran, modes of network organisation, illustration. |

In a locked-down world, society has become atomized. For those that can work remotely, the household has become the workplace. Rather than congregate in large and central locations, our working environments are now small clusters of individuals - the "node size" of the workplace has shrunk. At the same time, the workforce has become dispersed. Each of us is highly reliant on connectivity: we can only perform necessary tasks when able to digitally communicate with our colleagues and access internet resources.

The kind of workforce atomization we are experiencing today can have serious downsides. The change from working an office or library setting to working from home can be jarring to some, with many finding it difficult to concentrate. Aural and visual distractions may jostle with tasks for focus, along with household upkeep, interruptions by fellow occupants, and sometimes, a gnawing sense of loneliness. We have become used to the work-life dichotomy being mirrored in a separation of physical environments, and these environments are no longer discrete.

However, the lockdown work mode has its own boons. A departure from the nine-to-five allows us to be more flexible with hours, do away with antiquated dress formalities, and easily avoid people we do not want to talk to. Furthermore, some find that isolation from socializing opportunities begets excellent focus. Ludwig Wittgenstein decided to isolate himself in the Norwegian mountains after concluding that he had ‘solved philosophy’ with the Tractatus Logico-Philosophicus, showing that some find the benefits of solitude extend beyond productivity improvements. As Kazuhiko Namba said in 2018, working in proximity to the home obliterates the need for commuting, a massive burden on our economy. If commute times were evaluated in wage rates alone, they would represent a £148 billion loss to Britain, according to Randstad (2015). Commuting is also one of, if not the biggest causes of congestion - which cost Germany, Britain, and the United States $461 billion in 2017 alone (INRIX, 2018). Reducing the commute makes driving for other purposes more pleasant and cheaper, and may also even out property prices. One study found that decentralizing the workplace makes people choose to live as far away from population centres as possible, owing to cost dynamics (Simpson & van der Veen, 1992). This gives rise to a virtuous circle, whereby population density and property prices become ever-more evenly distributed, as employment opportunities stop being an issue for rural settlers.

This working mode, where labour site and residence intermix, is more reminiscent of the ancient world than the modern. In England, villages are typically spaced ten miles apart. A medieval villager could walk to fields up to five miles away each day, but no more if they wanted to return before sundown. Thus, village land would extend approximately five miles. Settlements were therefore spaced ten miles apart to avoid competing land claims – and the workplace closely surrounded, in a sense encompassed, the home. Ancient Roman villas were regularly constructed such that a shop or storefront occupied the front part of the building and living quarters the rear. Architect Kazuhiko Namba reflects Japan’s pre-industrial customs in his houses by placing labour space on the lower floor of the building, and living space on the upper floor (UTokyo, 2018).

The atomization of society that countries experience during lockdown is also a decentralization. In industries where workers can produce from home, the labour force distribution has morphed from a series of high-density cores occupying central buildings to a dispersed web of isolated individuals. This dispersed-web style of organization is a rich and promising form of organization that has already proved its merit in the digital space. Decentralized networks were first hypothesized in a paper by Paul Baran, which concerned the possibility of using “distributed” networks to protect nuclear weapons systems from attack. Because in a distributed network, each node is equally important as the rest, a targeted attack can only take down the whole system if many of the nodes are targeted. Coordinating strikes against lots and lots of nodes is infeasible and unlikely under most circumstances. Thus, a distributed network is impervious to the kinds of attack that a centralized model, where a single node supports the whole system, is very vulnerable to.

Today we might encounter the decentralized mode of operation through streaming services like Popcorn Time. The platform operates using Peer-to-Peer networking (P2P) to download movies and TV series from other people’s computers, taking the hassle and technicality out of torrenting for ordinary consumers. A distributed model is also used for the programs SETI@home and folding@home, which pool computing power from all the users that have the software active to perform calculations that aid in cosmological discovery and cancer research. There are even companies that operate cloud storage platforms which use the hard drives of private citizens scattered across the globe to store their customers’ data, rather than a centralized array of servers. All these ventures represent a break from the client-server networking model that predominates. Client-server organization creates a hierarchical structure in which a central server node connects with peripheral client nodes. The bulk of the computing power resources are located on the server side, and the client acts primarily as a receiver. The vast majority of things we download from or access on the internet come through star-shaped network structures like this, and in a sense the client-server model mirrors the producer-consumer dichotomy of Western capitalist society. On the other hand, P2P creates non-hierarchical structures in which every node is both a client and a server. Hence there is a mutual exchange of information, and a more equitable distribution of resources. Say for example you want to stream the finale of Modern Family. If you watch it through Netflix, the episode is stored on a powerful remote server that sends the video through your internet connection. If you watch it through Popcorn Time, the episode is stored on multiple “consumer” devices. The software works to collect chunks of the video from phones, laptops and PCs around the world, and assembles them into a continuous stream of playback. However, whilst the episode is downloading to your device, it is also helping to stream that episode to other devices. When part of the file has been acquired by a node in the network, any of the other nodes can start to download that part.

There are, as with anything, disadvantages with this structure of organization. Hosting files for others to download requires more processing power and better-quality connections than merely receiving a file, especially when multiple users are trying to access that file at once. The hegemony of client-server models has perpetuated computational inequality by making powerful, hidden server networks and passive, weak client devices the norm. Patterns of authority and control in society have manifested in the power relations displayed between digital devices. Consumer hardware, software and connectivity are therefore not engineered to participate in peer-to-peer networks. Enfeebled by this and in part by capitalist incentives to maximize profits, decentralized and distributed applications face an uphill battle in gaining widespread acceptance. Few recognize the loss of the franchise that has occurred as computers and models of interaction with them have evolved from their earliest antecedents to the programmatically lobotomized forms we have today.

However, as technological capabilities and imagination improve, centralization begins to seem like a problem and even a threat. Russian writer Yevgeny Zamyatin painted a picture of a totalitarian state in which the walls of all buildings are made of glass, creating a literally transparent society. Although the intentions of this systematic design were to foster a communitarian spirit by breaking down the boundaries of privacy between people, in his 1921 novel it ultimately resulted in a dispassionate existence where every member feels unfree to perform individual acts. The social mediatized, data driven world we live in dissolves our ability to act originally by allowing the screens to proverbially watch back at you. In the Orwellian present, the volumes of data collected on every one of us are so large that entire swathes of our lives could be artificially reconstructed from data that is stored on remote servers elsewhere. Bit by bit, we are being digitally cloned so that advertisers and product pushers can perform virtual experiments on us to determine our preferences, find what makes us tick, and infiltrate the neurological processes that compel us to reach for our wallet. What’s more, these digital clones of ourselves, stored in central locations, are not in our possession, and we cannot claim ownership over them. Not only does this scale of data collection and application have profound implications for who we are and what thoughts we think, but it also allows corporate control to take captive an ever-greater portion of our lives.

The 5G debate has also shed light on the problems of centralized control. Huawei has been barred from building critical communications infrastructure across NATO countries because of a growing recognition of the subterranean warfare raging between West- and East-aligned powers. As counterinsurgency expert David Kilcullen remarks, whilst the West is restrained in its ability to wage war on multiple fronts by Congress, international law, and the European Convention on Human Rights, non-Western powers can engage in multifaceted conflict through technological, informational, cultural and economic avenues (2020). Thus, although China does not pose a violent threat to occidental interests, the issues with a China that controls not only Western electronics but also the very networks that underpin advanced society are becoming increasingly apparent. There are inherent flaws with production methods that rely on a single manufacturer, whether foreign or domestic. When that manufacturer – the central “node” – is infiltrated, the whole system becomes vulnerable. Indeed, one of the recent proposals to address 5G security issues is to make the hardware and software open source. This would make the schematics for the infrastructure components freely accessible, and thus open them up to the scrutiny of the entire development community. The OpenAirInterface describes itself as a ‘5G software alliance for democratizing wireless innovation’. With the backing of hundred-billion-dollar corporations like Qualcomm and Facebook, along with prestigious educational institutions across the world, the decentralized development of 5G that the group advocates for seems very likely.

Decentralization is something that can benefit all of us, even if the atomization we experience during lockdown can be painful. By creating a freer digital experience, we may be able to address economic and social inequalities. A system in which each device is equally capable of producing as well as consuming, of giving as well as taking, claws back power from multinational entities and befits a kind of independence that the current system lacks. This could help bring us closer to the kind of meritocracy that the American patriots first envisioned, rather than the warped and inverted kind that proliferates. On the face of it, centralization in a purely physical sense confers the major benefit of efficiencies of scale, with multiplicative effects on productivity and innovation. Scientific and technological discoveries are disproportionately clustered in big, developed cities. The tight and densely interwoven network structures of metropolitan areas produce more than the sum of their parts: a whole host of experts with deep knowledge on esoteric, specialist topics can congregate, collaborate, and learn from each other actively, to produce bold ideas. However, the basic virtue of cities is not their central nature, but the high density of good quality links between people that it affords. Urban individuals can directly communicate with millions of others. As direct in-person contact is superior to the technologically enabled kind, the countless opportunities for direct contact with others mean that urban areas become sites for innovation.

The advantages of face to face encounters are twofold, and both can be replicated with technology. Firstly, when communicating in person, much greater volumes of information are transmitted than through digital at present. A great deal of what we say is conveyed through subtle body language, gestures, intonation and prosody. If we can capture this lost information, we can make digital rendezvous both more satisfying and more effective. The second benefit of real-life communication is that it possesses spontaneity. Accidents, chance encounters, and close contact with strangers are much rarer online. These occurrences allow information to flow between people in a fluid, ever-changing, and unpredictable way. Many an outlandish, improbable idea and discovery can be attributed to accident. Philosopher Paul Thagard, writing on the process of scientific innovation, says that ‘serendipity may provide a surprising or curiosity-inducing event that inspires questioning, as when Newton’s perception of the fall of an apple moved him to wonder who objects fall toward the earth’s centre…[and] when a search is underway, serendipity may provide a representation or operator that was not part of the original problem place, as when Goodyear discovered vulcanization’ (1998). Digital communications today suffer from a failure to represent indirect signalling, and a lack of unintentional interaction. There are some exceptions, like the virtual bars of traktor.cc which has become popular in lockdown Ukraine. However, although you are afforded one type of contact with online strangers, you are not given the opportunity to spill your drink on them, unintentionally dance with their girlfriend, or pick a bloody fight. On a serious note, we really do need digital interaction to improve, to replicate chance and randomness, and non-literal communication, if we are to expect it to live up to its real-life counterpart.

The ability to have fully-fleshed interactions with others, through a digital system that democratizes the relations between producer and consumer, would revolutionize modern society. Lockdowns like this would be a lot more bearable. But also, it may fundamentally reshape the way that we organize ourselves. Humans are social animals, and communications – whether personal or professional – are the lynchpin of our existence. But the models of electronic communication we have today are not designed to maximize the benefits we can reap from them. Decentralized communications will require a radical rethink of how networks are built, and user experiences are designed. Nonetheless, the payoffs will be immense.

Originally appeared on How the World Recovers

Comments

Post a Comment